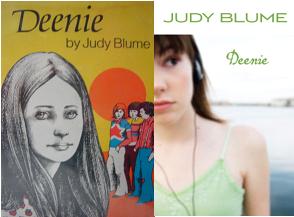

The first young adult (YA) novel I ever read that had to do with body image was Judy Blume’s Deenie (1973). In it, 13-year-old Wilmadeen “Deenie” is the “pretty one” of the family, the one whose mother dreams will be a model someday. When Deenie is diagnosed with scoliosis and required to wear a back brace, she struggles with self-image and self-acceptance—worrying that her crush won’t find her attractive, that she will be an object of social ridicule at school, and that she won’t ever get to be a model. Instead, Deenie negotiates a new sense of self, new relationships with her parents and sister, new friendships, and contemplates a career as an orthopedist, realizing that perhaps she never wanted to be a model after all.

For its explicit mentions of masturbation and menstruation, Deenie is one of the most frequently challenged and banned books of all time. But its real radicalism is as an early example of how teen literature can tackle critical issues including body image and body self-acceptance. In other novels, including Blubber (1974) and Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret (1970), Blume similarly tells young women’s coming of age stories, and of the accompanying social and environmental pressures therein. (However, in Blume’s Forever (1975), a novel about the first sexual experience, her portrayal of the ultra-thin protagonist is left unexamined, which is soundly critiqued by Beth Younger in her book Learning Curves: Body Image and Female Sexuality in Young Adult Literature.)

Also published in the same era, Paula Danzinger’s The Cat Ate My Gymsuit (1974) similarly addressed issues of self-image, this time through the point of view of 13-year-old Marcy Lewis, a self-described “baby blimp with wire frame glasses and mousy brown hair.” However, Marcy is more than simply “fat” and her personal growth is vis-à-vis more than just body self-acceptance. As Marcy evolves, she ends up being an activist for change in the small community of her school.

An entire group of current-day YA literature tackles issues of body image, similarly generating controversy. For example, author Laurie Halsie Anderson’s novel Wintergirls (2009), which is written from the point of view of a young woman with severely disordered eating, has caused great uproar among parents and educators.

To read the rest of this essay, please go to Adios, Barbie!