In most countries, there is a culture of taboo and secrecy around menstrual health and hygiene. Just think of all those ridiculous commercials for sanitary products that allow you to engage in activities ‘without anyone knowing’ you are menstruating – even if you are wearing white spandex or leaping in the air or whatever. Last year, a British company named Bodyform made this brilliant commercial to try and debunk some of the secrecy around ‘period talk’ but still, we persist in treating menstruation like a hush-hush taboo:

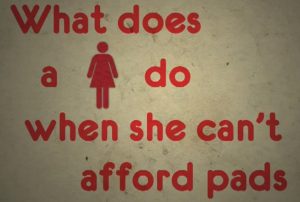

This doesn’t seem like such a big problem until we realize that menstrual supplies – and their lack – is a critical issue of dignity, mobility, and human rights for girls and women around the world.

Take the importance of menstrual supplies to girls’ education.

During a meeting for an upcoming TEDx event at Sarah Lawrence College, I was listening to a graduate student named Ellie Roscher describe a successful educational model in an impoverished slum outside Nairobi, Kenya. Run by a local man who wanted to make sure that girls from his community could get the same opportunities as boys, The Kibera Girls Soccer Academy understands the local pressures that keep girls from higher education, including the fact that a free education is not actually free. Families who chose to send their girls to school in deeply impoverished communities around the world are losing their labor – either in the form of outside income or domestic labor taking care of family members and cooking meals. At the very least, families have to pay for the food and supplies that their school-going children require.

And so, The Kibera Girls Soccer Academy not only provides the girls with what they need to study, but offers all students and teachers one meal every day, as well as sanitary supplies. This last fact may seem startling. Sanitary supplies? How can that be as important as pencils, or books, or a warm, nourishing meal? Yet, without sanitary products, girl students in the Global South are often prevented from leaving their homes and attending school. Why? Firstly, and most obviously, many women living in poverty cannot afford good quality products and make do with rags or other non-absorbent materials, such as bark or grasses.

But there are local initiatives addressing this problem. For instance, a project in the Amuru and Gulu regions of Uganda has students staying after school to make sanitary pads using cheap, readily available local materials. These absorbent pads can be washed and used again, and their availability has helped curb the rampant absenteeism from school that is common among adolescent girls during their menstrual periods. Another example is the sustainable health enterprise (the she28campaign), which is developing a franchise model to make and distribute ecologically-friendly sanitary products made from local materials like banana fronds.

To read the rest of this essay please visit Adios, Barbie!