What if everyone was beautiful? No, I don’t mean inner beauty, prettiness that shines from the inside out. I mean, wide eyes, perfect noses, proportionate bodies, and symmetrical faces. The same approximate height, weight, skin color? Could making everyone look the same even the social and economic playing fields?

But human variety is important—it would be boring for everyone to be conventionally pretty, you say.

Well, what if we upped the stakes? What if making everyone beautiful could help stop bullying or eliminate eating disorders? What if it eradicated racism, prejudice, or even brought an end to all war and conflict?

Would it be worth it then?

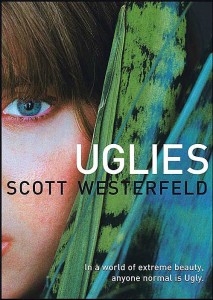

Young adult (YA) author Scott Westerfeld spins these possibilities, and more, into his novel Uglies. In so doing, he follows in the tradition of other science fiction/speculative fiction writers who use settings on different planets or in future dystopian Earths to examine sociopolitical problems in our present day lives. African American sci-fi legend Octavia Butler used many of her short stories and novels to examine race, gender, power, and slavery; similarly, The Handmaid’s Tale novelist Margaret Atwood imagined sexism taken to the extremes of reproductive terrorism in her novel—a world where women are literally reduced to being walking wombs.

In Uglies, Westerfeld seems to be undertaking a similar project but with body image politics. His novel is set in a futuristic world where everyone on their 16th birthday undergoes an extreme makeover, the super-duper plastic surgery edition. Until they have this bone-crunching, face-rearranging operation, teens are “uglies” and have to live in (the slightly unimaginatively named) “Uglytown” watching the glamorous post-surgical “pretties” across the river in high tech “New Prettytown” leading wonderful lives of (competition-less, racism-less, prejudice-less, aggression-less) happiness and endless partying.

In a sense, Westerfeld’s dystopian world is teen reality writ large—the feeling of being on the outside looking in, waiting for your life to start, wishing one could be ‘like everyone else.’ And in that sense, the novel is about learning to be ‘happy with oneself,’ and embracing one’s autonomy rather than following the herd.

At the beginning of the novel, Westerfeld’s 16-year-old protagonist, Tally, can’t wait to turn pretty. But when her new friend Shay runs away, she faces a serious choice: to either join her friend in a rag-tag community of people who have chosen to remain “ugly forever,” or turn in these rebels to the authorities in exchange for her coveted operation.

To read the rest of this essay, please visit Adios, Barbie